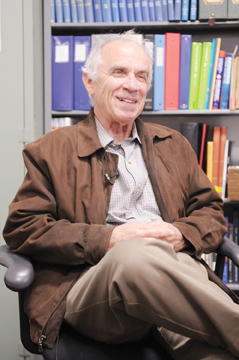

Darwin Payne, professor emeritus and official SMU centennial historian, was a 26-year-old reporter for The Dallas Time Herald the day John F. Kennedy was assassinated.

Payne was assigned to cover the Kennedy’s arrival at Love Field Airport and was struggling with the beginning of an article on Jackie Kennedy’s attire when he heard the news that shots had been fired in Dealey Plaza.

He and another reporter were told to run the five blocks to the area.

“When we got there the scene was one of bedlam,” said Payne, who taught journalism at SMU for 30 years. “There were lots of people around in tears, police officers, some with rifles, there was a fire truck there. So I started interviewing people on the scene.”

Several women Payne interviewed said their boss had taken pictures of the assassination. That boss was Abraham Zapruder, the owner of the famous video footage that captured Kennedy’s assassination.

The women took Payne to Zapruder’s office where he interviewed him for 45 minutes. Payne said Zapruder was in tears most of the interview and that he wanted to give the film to the secret service or FBI. When those agencies arrived at Zapruder’s office, Payne was not allowed in the room.

Payne went to the Texas School Book Depository, where reporters were allowed to observe the sixth floor and Lee Harvey Oswald’s “sniper’s nest.”

Payne returned to the newspaper’s office and was then sent to 1026 N. Beckley St. in Oak Cliff, a rooming house where Oswald had been living under the name “O.H. Lee.”

Payne interviewed the owner of the rooming house and the residents who he said described Oswald as standoffish. That night Payne stayed up until 2 a.m. to write a story about everything he knew and had found out about Oswald. That story ran in Saturday’s Dallas Times Herald.

Saturday night was Payne’s regular night at the police station, which he said was full of journalists awaiting updates on Oswald.

“That night you would see Oswald maybe a couple of times,” Payne said. “They’d take him in and out of the homicide office back up to the temporary jail at the top of the police station.”

Payne stayed at the station until around 2 a.m. and said the police chief told reporters to come back by 10 a.m. and “you won’t miss anything” regarding Oswald, who had been formally charged for murdering Officer JD Tippit and President Kennedy.

Payne woke up Sunday around noon to the news reports of Jack Ruby shooting and killing Oswald. Payne visited Ruby’s apartment that day but said “in the days thereafter almost every reporter was involved in covering aspects of the assassination.”

Payne described 1963 Dallas as a hotbed of right-wing extremists.

“We feared in Dallas that something would happen on that visit,” he said.

“Dallas had been prepared to try to give a good, positive reception to the president. Otherwise, the reputation of the city would have been further deteriorated.”

Payne cited behavior of former general Edwin A. Walker and Frank McGehee, head of the National Indignation Convention, as examples of strong conservative voices in

the city.

“There were all sorts of extreme right wing people who didn’t hesitate to demonstrate and try to drown out opposing voices,” Payne said.

He said after the assassination, however, those voices “virtually disappeared.”

“I think they realized somehow the ‘city of hate’ reputation that Dallas had received came just not because of Oswald but because of those groups.”

Payne said the election of moderate democrat and 1963 Dallas Mayor Earl Cabell over Bruce Alger to Congress showed a shift in political thought. In 1963, eight of the nine Texas representatives were republicans.

“In the election that followed 1964, all eight [republican representatives] lost and we had a clean slate of democrats going to the state legislature,” Payne said. “So you had that immediate reversal of politics. You saw a great moderation of political thought in Dallas.”

Payne does not believe there was a conspiracy surrounding the assassination and conducted a poll of about 40 reporters who also covered the event. Payne said the results of the poll showed only two or three journalists that believed there was a conspiracy.

Payne reflected on his thoughts during those days of historical significance.

“On that very day, I was thinking, ‘50 years from now there will be a big commemoration of this event, of President Kennedy, and I likely will be there,’” Payne said.

Payne will not be attending the commemoration in Dealey Plaza today, but said he was glad he was there 50 years ago.

“As tragic as the incident was, as horrifying as it was, as much as I liked Kennedy at the time, I felt lucky,” Payne said. “I was fortunate to have been there and been involved in an event of that magnitude.”

As the official SMU centennial historian, Payne wrote a history of SMU that will be published in early 2016.